What $5 Trillion Buys: US Healthcare Spending vs. Global Outcomes

INSIGHTS

Enoma Ojo (2026)

1/3/20264 min read

What $5 Trillion Buys: US Healthcare Spending vs. Global Outcomes

Across the world, healthcare outcomes have improved dramatically over the past century, driven by advances in medicine, public health, and targeted investments in health systems. Global life expectancy has risen in nearly every region, reflecting major reductions in infectious diseases, maternal mortality, and childhood deaths. According to global health analyses, these gains are especially notable in lower‑income countries, where improvements in sanitation, vaccination, and primary care have helped narrow, but not eliminate, the gap between the world’s healthiest and least healthy populations. Despite this progress, global health outcomes remain deeply uneven. Life expectancy still varies by more than 20 years between the highest‑performing countries—such as Japan and parts of Western Europe—and regions where life expectancy remains below 60 years, particularly in parts of Sub‑Saharan Africa. The World Health Organization’s annual health statistics show that these disparities extend across nearly every major indicator, including child mortality, chronic disease burden, and access to essential health services. In many regions, preventable diseases continue to account for a large share of deaths, underscoring persistent gaps in healthcare infrastructure and economic development.

The global burden of disease also highlights a shifting landscape. As infectious diseases decline, non‑communicable diseases—such as heart disease, diabetes, and cancer—now account for the majority of global mortality. This transition places new pressure on health systems, which must balance the demands of aging populations, chronic disease management, and rising healthcare costs. Countries that invest strategically in preventive care, early detection, and primary care infrastructure tend to achieve better outcomes at lower cost, demonstrating the strong relationship between targeted spending and population health improvements. Yet even with these insights, the world continues to grapple with the question of how much healthcare spending is enough—and how effectively that spending translates into healthier lives. Some nations achieve exceptional outcomes with moderate investment, while others spend far more with comparatively weaker results. This global context sets the stage for examining the United States, where healthcare spending has reached nearly $5 trillion, yet key health outcomes lag behind many peer nations. Understanding how global health systems convert resources into results provides a critical lens for evaluating what Americans truly receive for the world’s highest healthcare expenditure.

Against this global backdrop, one question becomes increasingly important: how effectively do nations convert healthcare spending into healthier lives? Around the world, many countries achieve strong outcomes with moderate investment, while others spend far more with less to show for it. This contrast sets the stage for examining the United States, where healthcare spending has surged toward $5 trillion, yet key health indicators lag behind many peer nations. Understanding how global systems translate resources into results provides essential context for evaluating what Americans truly receive for the world’s highest healthcare bill. While countries around the world continue refining their health systems to achieve better outcomes with strategic, efficient investment, the United States stands out for a very different reason: the sheer scale of its spending. No nation allocates more money to healthcare, yet few high‑income countries see such modest returns on that investment. This disconnect between cost and outcome makes the U.S. an important case study in how resources are used, and sometimes misused, within modern health systems. As global trends show what is possible with balanced, prevention‑focused approaches, the American experience raises a critical question: What exactly does $5 trillion in annual healthcare spending buy, and why do the results fall short of expectations?

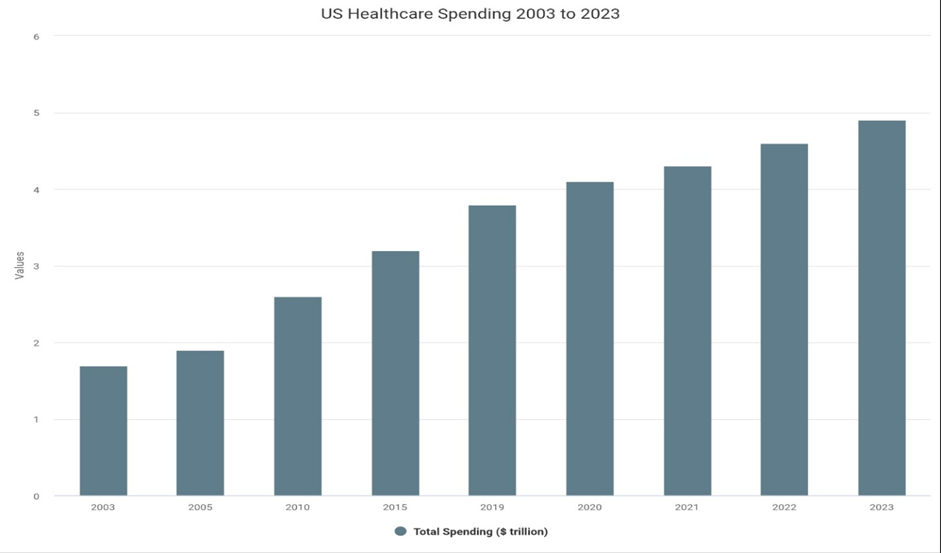

The United States is on the verge of spending $5 trillion a year on healthcare, more than any nation in human history. In 2023 alone, U.S. health expenditures reached $13,432 per person, nearly double the average of other wealthy OECD countries. As of 2022, the US spent 16.6 percent of its GDP on healthcare, compared to 9.2 percent of OECD average. This level of spending exceeds the GDP of most nations, yet it has not translated into better health for the American people. Instead, it has exposed a deeper truth: the U.S. pays more than anyone else, but gets less in return. The United States has seen extraordinary growth in healthcare spending over the past two decades. According to KFF’s analysis of National Health Expenditure (NHE) data, total U.S. health spending rose from about $1.7 trillion in the early 2000s to $4.9 trillion in 2023. CMS confirms the 2023 figure at $4.9 trillion, or $14,570 per. From roughly $6,000 per person in the early 2000s to $14,570 per person in 2023

Across the world’s richest countries, healthcare spending rises with national wealth, but even among these peers, the U.S. stands in a category of its own. Other high‑income nations spend about half as much per person on healthcare, averaging $7,393 annually. Yet these countries consistently deliver longer life expectancy, lower maternal and infant mortality, and fewer deaths from preventable conditions. The U.S. is the only high‑income nation without universal coverage, and it shows in the outcomes. The Commonwealth Fund’s global comparison is blunt: the U.S. ranks last in overall health system performance among high‑income nations, with the lowest life expectancy, the highest rates of avoidable deaths, and the highest maternal and infant mortality. These are not marginal differences, they are systemic failures that persist despite unprecedented spending. The paradox is clear: the U.S. invests more money into healthcare than any other country, yet delivers some of the weakest results. This disconnect raises a fundamental question: What exactly are Americans buying with $5 trillion? The answer is not more doctor visits or more hospital care. In fact, Americans see physicians less often than people in most peer countries and have fewer hospital beds per capita. What drives U.S. spending is not volume, it’s prices. Everything from hospital stays to prescription drugs to administrative overhead costs significantly more in the U.S. than anywhere else in the developed world. As national health expenditures continue to climb, the stakes are rising. The U.S. doesn’t just have a healthcare spending problem — it has a health value problem. If $5 trillion cannot buy longer lives, healthier communities, or equitable access to care, then the system is not merely expensive; it is inefficient by design. Understanding this gap between spending and outcomes is the first step toward reshaping a system that delivers real value for every dollar invested.

© 2026 Enoma Ojo. All Rights Reserved. No part of this content or imagery may be reproduced, distributed, or transmitted without prior written permission.